Learn through the super-clean Baeldung Pro experience:

>> Membership and Baeldung Pro.

No ads, dark-mode and 6 months free of IntelliJ Idea Ultimate to start with.

Last updated: March 18, 2024

Swap space is a memory virtualization concept. It’s a strategy to mitigate memory starvation when a system is running out of memory. To employ it, Linux moves or swaps out blocks of non-critical memory to disk and swaps them back in on demand. Notably, Linux can use either a swap partition or a swap file for this type of memory when real memory is full.

In this tutorial, we’ll compare swap partitions to swap files for performance.

Again, swap space is a piece of our disk that handles Random-Access Memory (RAM) overflow conditions.

Let’s see the typical reasons for RAM overflow conditions:

In such cases, to improve performance, Linux swaps pages that aren’t in constant use. Thus, the kernel frees more available memory for other processes. In fact, we can see the swap activity using the free command:

$ free -h

total used free shared buff/cache available

Mem: 7.8Gi 5.4Gi 804Mi 122Mi 383Mi 1.1Gi

Swap: 4Gi 2.1Gi 1.9GiMoreover, using swap space doesn’t only serve to enhance memory. It also stores data from RAM when hibernating.

So, the system improves performance by swapping out inactive memory pages, thus keeping often-used data in the cache. In addition, swap space prevents failure to allocate memory, especially on systems with low memory.

However, there are drawbacks as well:

Still, when we increase the memory size, it allows the system to run more programs. As such, we’ll need to adjust the swap space to carry more data when the system hibernates.

Next, let’s see how to find out the kind of swap space in use on our system.

The free command shows the size of the swap space. However, it doesn’t specify whether the swap is a partition or a file.

To check the kind of swap space that’s in use, we can run the swapon command:

$ sudo swapon --show

NAME TYPE SIZE USED PRIO

/swapfile file 4096M 2150.4M -1Notably, the swapon tool doesn’t show any output if the system has no swap space.

Now, we can compare swap partitions to swap files in terms of performance.

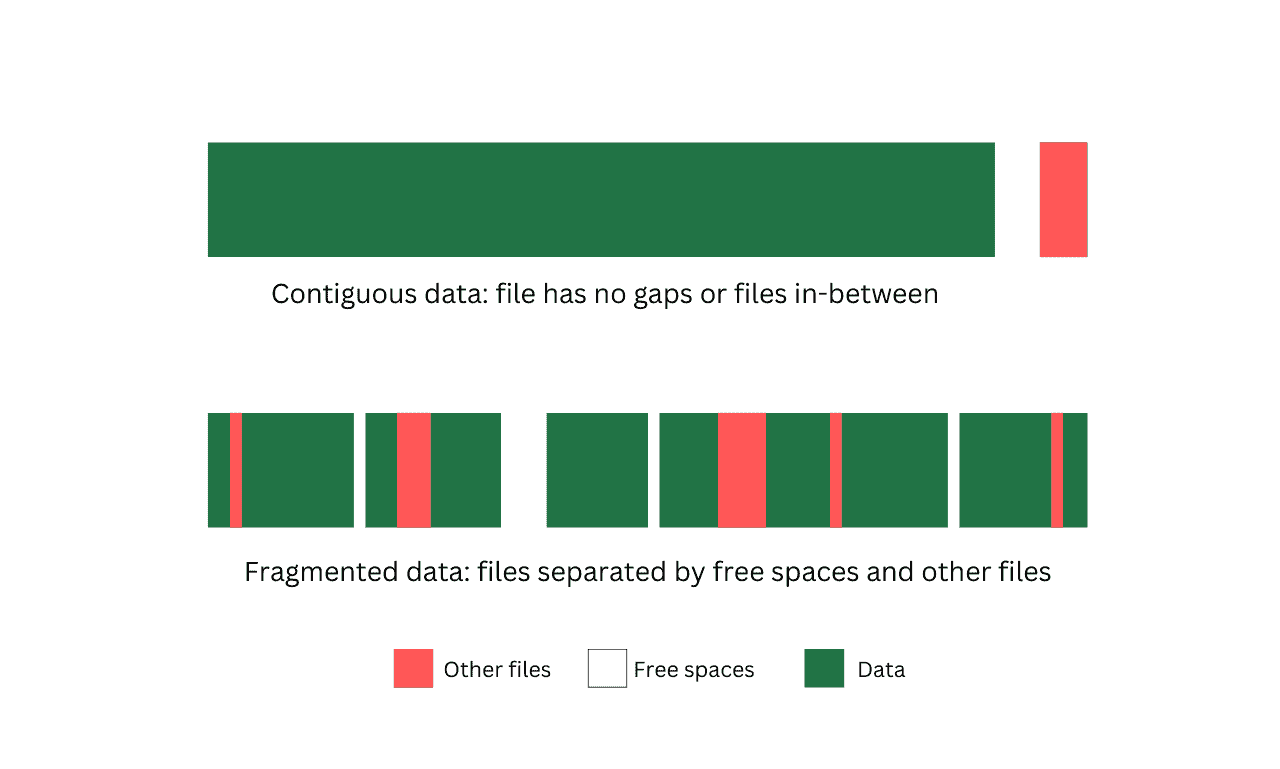

A benefit of using swap partitions on Hard Disk Drives (HDDs) is the ability to place them on contiguous HDD areas. This improves performance by increasing data throughput or decreasing seek time.

When talking about contiguous memory, we refer to sectors next to one other on a computer hard drive. Further, writes are usually contiguous, provided there’s enough space.

However, if there aren’t enough sectors, the data is written to multiple locations on the disk, resulting in fragmented data. This fragmentation would reduce performance on a traditional hard drive, but would have less of an impact on a Solid State Drive (SSD):

Notably, throughput and seeking are often faster toward the edge of the disk. The performance difference results from the fact that this part has more sectors per cylinder yet spins at the same speed.

Also, creating the swap file when the filesystem is fresh and empty usually keeps it contiguous and improves performance. In fact, the kernel doesn’t allow using a sparse file as a swap file.

From the end-user perspective, swap files in higher Linux kernel versions are virtually as fast as swap partitions. Of course, the swap file should be contiguous to provide the same speed as a partition.

Also, there are a few things that the kernel does to increase the performance of swap files:

Further, in older Linux kernel versions like 2.4, swap files can lead to system slowdowns. Basically, the kernel allocates memory from the main page allocator when performing a swap out. When doing many swap-outs, this causes extra reads and writes on the system drive.

Importantly, when the system starts using the swap file on the drive, performance may suffer because both SSDs and HDDs are much slower than RAM.

Further, let’s compare the flexibility of a swap file versus a swap partition.

The administrative flexibility of swap files can exceed certain advantages of swap partitions. For example, we can do these with a swap file:

In contrast, swap partitions are not as flexible, since we can’t enlarge a swap partition without disk management tools. These processes introduce various complexities and potential downtimes, along with time wastage and reboots.

Unlike a swap partition, a swap file is just a file. It’s flexible to handle. The system can stop using the file, resize it, and start using it again. Also, there are other advantages:

The handling of swap files is more flexible when compared to swap partitions for memory management on a system.

Finally, we’ll discuss the user preferences on swap.

In general, users and distributions prefer swap partitions to swap files.

For example, btrfs on Linux kernels before version 5.0 doesn’t support swap files at all. In fact, using a swap file for such a system may result in file system corruption.

Although we may use a swap file on btrfs for Linux kernel version 5.0 and higher, there are limitations:

Notably, the use of swap files is less common. Hence, they’re less tested when we compare them to swap partitions. This inadequate testing can lead to filesystem corruption bugs, like the one that appeared briefly in version 5.12-rc1.

According to Linus Torvalds, “all the normal distributions set things up with swap partitions, not files”.

In addition, “swapfiles tend to be slower and have various other complexity issues.”

In this article, we compared the swap file and swap partition for performance. Also, we saw the constraints that come with using a swap file or partition on a system.