1. Overview

Docker containers are used to run applications in an isolated environment. By default, all the changes inside the container are lost when the container stops. If we want to keep data between runs, Docker volumes and bind mounts can help.

, and how to manage and connect them to containers.

2. What Is a Volume?

2.1. The Docker File System

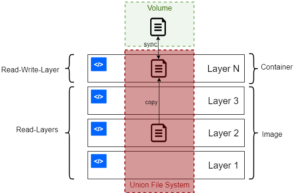

A docker container runs the software stack defined in an image. Images are made of a set of read-only layers that work on a file system called the Union File System. When we start a new container, Docker adds a read-write layer on the top of the image layers allowing the container to run as though on a standard Linux file system.

So, any file change inside the container creates a working copy in the read-write layer. However, when the container is stopped or deleted, that read-write layer is lost.

We can try this out by running a command that writes and then reads a file:

$ docker run bash:latest \

bash -c "echo hello > file.txt && cat file.txt"The result is:

helloBut if we run the same image with just the command to output the file’s contents:

$ docker run bash:latest bash -c "cat file.txt"

cat: can't open 'file.txt': No such file or directoryThe second run of the container runs on a clean file system, so the file is not found.

2.2. Bind Mounts

A Docker bind mount is a high-performance connection from the container to a directory on the host machine. It allows the host to share its own file system with the container, which can be made read-only or read-write.

This allows us to use a container to run tools that we don’t want to install on our host, and yet still work with our host’s files. For example, if we wanted to use a custom version of bash for a particular script, we might execute that script in a bash container, mounted to our current working directory:

$ docker run -v $(pwd):/var/opt/project bash:latest \

bash -c "echo Hello > /var/opt/project/file.txt"The –v option can be used for all forms of mounting and specifies, in this instance, the source on the host – the working directory in the output of $(pwd) – and the target mount point in the container – /var/opt/project.

After running this command, we will find file.txt in the working directory of our host machine. This is a simple way to provide persistent files between invocations of a Docker container, though it is most useful for when the container is doing work on behalf of the host.

One good use case for this would be executing various versions of a language’s build tools in Docker to avoid having conflicting installations on a developer machine.

We should note that $(pwd -W) is sometimes needed on Windows bash shells to provide the working directory in a form that the bash shell can pass to Docker.

2.3. Docker Volumes

A bind mount uses the host file system, but Docker volumes are native to Docker. The data is kept somewhere on storage attached to the host – often the local filesystem. The volume itself has a lifecycle that’s longer than the container’s, allowing it to persist until no longer needed. Volumes can be shared between containers.

In some cases, the volume is in a form that is not usable by the host directly.

3. Managing Volumes

Docker allows us to manage volumes via the docker volume set of commands. We can give a volume an explicit name (named volumes), or allow Docker to generate a random one (anonymous volumes).

3.1. Creating Volumes

We can create a volume by using the create subcommand and passing a name as an argument:

$ docker volume create data_volume

data_volumeIf a name is not specified, Docker generates a random name:

$ docker volume create

d7fb659f9b2f6c6fd7b2c796a47441fa77c8580a080e50fb0b1582c8f602ae2f3.2. Listing Volumes

The ls subcommand shows all the volumes known to Docker:

$ docker volume ls

DRIVER VOLUME NAME

local data_volume

local d7fb659f9b2f6c6fd7b2c796a47441fa77c8580a080e50fb0b1582c8f602ae2fWe can filter using the -f or –filter flag and passing key=value parameters for more precision:

$ docker volume ls -f name=data

DRIVER VOLUME NAME

local data_volume3.3. Inspecting Volumes

To display detailed information on one or more volumes, we use the inspect subcommand:

$ docker volume inspect ca808e6fd82590dd0858f8f2486d3fa5bdf7523ac61d525319742e892ef56f59

[

{

"CreatedAt": "2020-11-13T17:04:17Z",

"Driver": "local",

"Labels": null,

"Mountpoint": "/var/lib/docker/volumes/ca808e6fd82590dd0858f8f2486d3fa5bdf7523ac61d525319742e892ef56f59/_data",

"Name": "ca808e6fd82590dd0858f8f2486d3fa5bdf7523ac61d525319742e892ef56f59",

"Options": null,

"Scope": "local"

}

]We should note that the Driver of the volume describes how the Docker host locates the volume. Volumes can be on remote storage via nfs, for example. In this example, the volume is in local storage.

3.4. Removing Volumes

To remove one or more volumes individually, we can use the rm subcommand:

$ docker volume rm data_volume

data_volume3.5. Pruning Volumes

We can remove all the unused volumes with the prune subcommand:

$ docker volume prune

WARNING! This will remove all local volumes not used by at least one container.

Are you sure you want to continue? [y/N] y

Deleted Volumes:

data_volume4. Starting a Container with a Volume

4.1. Using -v

As we saw with the earlier example, we can start a container with a bind mount using the -v option:

$ docker run -v $(pwd):/var/opt/project bash:latest \

bash -c "ls /var/opt/project"This syntax also supports mounting a volume:

$ docker run -v data-volume:/var/opt/project bash:latest \

bash -c "ls /var/opt/project"As our volume is empty, this lists nothing from the mount point. However, if we were to write to the volume during one invocation of the container:

$ docker run -v data-volume:/var/opt/project bash:latest \

bash -c "echo Baeldung > /var/opt/project/Baeldung.txt"Then our subsequent use of a container with this volume mounted would be able to access the file:

$ docker run -v data-volume:/var/opt/project bash -c "ls /var/opt/project"

Baeldung.txt

The -v option contains three components, separated by colons:

- Source directory or volume name

- Mount point within the container

- (Optional) ro if the mount is to be read-only

4.2. Using the –mount Option

We may prefer to use the more self-explanatory –mount option to specify the volume we wish to mount:

$ docker run --mount \

'type=volume,src=data-volume,\

dst=/var/opt/project,volume-driver=local,\

readonly' \

bash -c "ls /var/opt/project"The input to –mount is a string of key-value pairs, separated by commas. Here we’ve set:

- type – as volume to indicate a volume mount

- src – to the name of the volume, though this could have been a source directory if we’d been making a bind mount

- dst – as the destination mount point in the container

- volume-driver – the local driver in this case

- readonly – to make this mount read-only; we could have chosen rw for read/write

We should note that the above command will also create a volume if it does not already exist.

4.3. Using –volumes-from to Share Volumes

We should note that attaching a volume to a container creates a long-term connection between the container and the volume. Even when the container has exited, the relationship still exists. This allows us to use a container that has exited as a template for mounting the same set of volumes to a new one.

Let’s say we ran our echo script in a container with the data-volume mount. Later on, we could list all containers we have used:

$ docker ps -a

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

4920602f8048 bash "docker-entrypoint.s…" 7 minutes ago Exited (0) 7 minutes ago exciting_payneWe could run our next container, by copying the volumes used by this one:

$ docker run --volumes-from 4920 \

bash:latest \

bash -c "ls /var/opt/project"

Baeldung.txt

In practice –volumes-from is usually used to link volumes between running containers. Jenkins uses it to share data between agents running as Docker containers.

5. Conclusion

In this article, we saw how Docker normally creates a container with a fresh filesystem, but how bind mounts and volumes allow long-term storage of data beyond the container’s lifecycle.

We saw how to list and manage Docker volumes, and how to connect volumes to a running container via the command line.