Learn through the super-clean Baeldung Pro experience:

>> Membership and Baeldung Pro.

No ads, dark-mode and 6 months free of IntelliJ Idea Ultimate to start with.

Last updated: May 12, 2023

An Operating System (OS) process interacts with other processes running in the same system to complete a common task. Processes that interact with other processes are known as co-operating processes.

Based on the Inter-Process Communication (IPC) strategies implemented by a process, it can either share its address space with other processes or communicate through message exchange. In the former technique, it is critical to control the communication as both processes share a common address space.

This controlling of process communication is known as synchronization. Without proper synchronization, processes may read obsolete data or overwrite other process data.

Semaphore and mutex are two mechanisms through which we can implement synchronization and manage process coordination. In this article, we’ll look into these two synchronization utilities and compare various characteristics.

Before discussing semaphore and mutex, let us understand the critical-section problem.

Let us assume that we have a system that contains n processes. Each of these processes has a segment of code in which the process may perform a common variable update, a table update, or write into a file. This segment of code is referred to as the critical section of a process.

The essential characteristic of the critical section is that once a process starts executing its critical section, no other process is allowed to execute its critical section. That is, no two processes can execute their critical section simultaneously. This critical section problem is to design a protocol so that processes can use cooperation.

Each process needs to obtain permission to enter its critical section. The piece of code that implements the permission is known as the entry section. Similarly, the piece of code that implements the exit of the critical section is known as the exit section.

The solution to a critical-section problem needs to satisfy the following criteria:

There are several utilities to solve the critical section problem in an OS. The mutual exclusion (mutex) locks or the mutex is the simplest solution. We use the mutex locks to protect the critical section and prevent the race conditions. A process needs to acquire the lock before it accesses its critical section, and it releases the lock once it finishes the execution of the critical section.

These two functionalities to acquire and release locks are represented through two functions – acquire() and release(). The acquire function acquires the lock, and the release releases the lock. A mutex lock has a boolean variable that decides whether the lock is available or not. If the lock is available, then the acquire() method succeeds, and the lock is considered as not available. Any process that tries to access an unavailable lock is blocked until the lock is released.

The following pseudo-code shows the acquire() method:

algorithm acquire():

// OUTPUT

// Acquires a resource if available, otherwise busy waits

while not available:

// busy wait

available <- false

The following pseudo-code shows the release() method:

algorithm release():

// OUTPUT

// Releases a resource making it available

available <- true

The major drawback of a mutex lock is that it lets the thread spinlock if the lock is not available.

While one thread has acquired the lock and is in its critical section, all other threads attempting to acquire the lock are in a loop where the thread periodically checks whether the lock is available. Thus, it spins for the lock and wastes CPU cycles that could have been used by some other threads productively.

This is a major problem in a single CPU machine. Spinlock is also known as busy waiting as the thread is “busy” waiting for the lock.

Although mutex locks suffer from the issue of spinlock, they do have an advantage. As the process spinlocks in the CPU, it eliminates the need for the process context switch, which otherwise would have required.

Context switch of a process is a time-intensive operation as it requires saving executing process statistics in the Process Control Block (PCB) and reloading another process into the CPU. There are multi-processor CPUs where one process can spin in one processor core, and another can execute their critical section. Thus, a spinlock of short duration in some scenarios is more useful than a process context switch.

A semaphore is another utility that also provides synchronization features similar to mutex locks but is more robust and sophisticated.

A semaphore is an integer variable that, apart from initialization, is accessed through two standard atomic operations – wait() and signal(). The wait() operation is termed as P, and the signal() operation is termed as V.

Let’s take a look at the wait() operation:

algorithm wait(S):

// INPUT

// S = Semaphore or a similar counting mechanism

// OUTPUT

// Decrements the semaphore if it's greater than 0, otherwise busy waits

while S <= 0:

// busy wait

S <- S - 1

Finally, let’s look at the signal() operation:

algorithm signal(S):

// INPUT

// S = Semaphore or a similar counting mechanism

// OUTPUT

// Increments the semaphore

S <- S + 1

All operations to the integer value of the semaphore in the wait() and signal() executed atomically. That is, once one process modifies the semaphore value, no other process can simultaneously modify the same semaphore value.

Based on the value of the semaphore S, it is classified into two categories – counting semaphore and binary semaphore. The value of a counting semaphore can range over 0 to a finite value. Whereas, the value of a binary semaphore can be between 0 and 1.

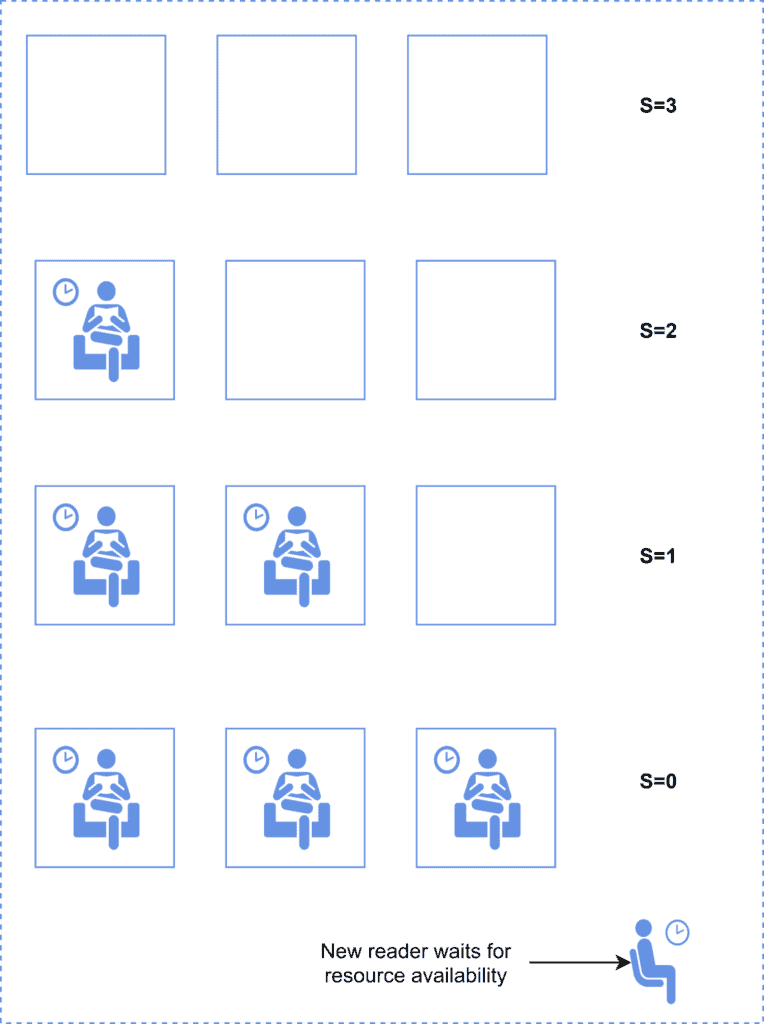

Counting semaphores can control the N number of instances of a given resource. Let us explain the counting semaphore with an analogy.

Let us assume there exists a library with three study rooms, and there is a librarian who holds ten keys, each one for a different room. Once a reader requires access to a room, they need to obtain a key to use the room. Once a reader is done with their usage, they return the room key to the librarian. Once all rooms are in use, a new reader needs to wait until a room is vacated by an existing reader.

In the above example, the resource is a room, and there are ten instances of it. These instances are managed through a counting semaphore which is initialized with ten. This semaphore value is controlled through the semaphore’s wait() and signal() methods. The following diagram illustrates this:

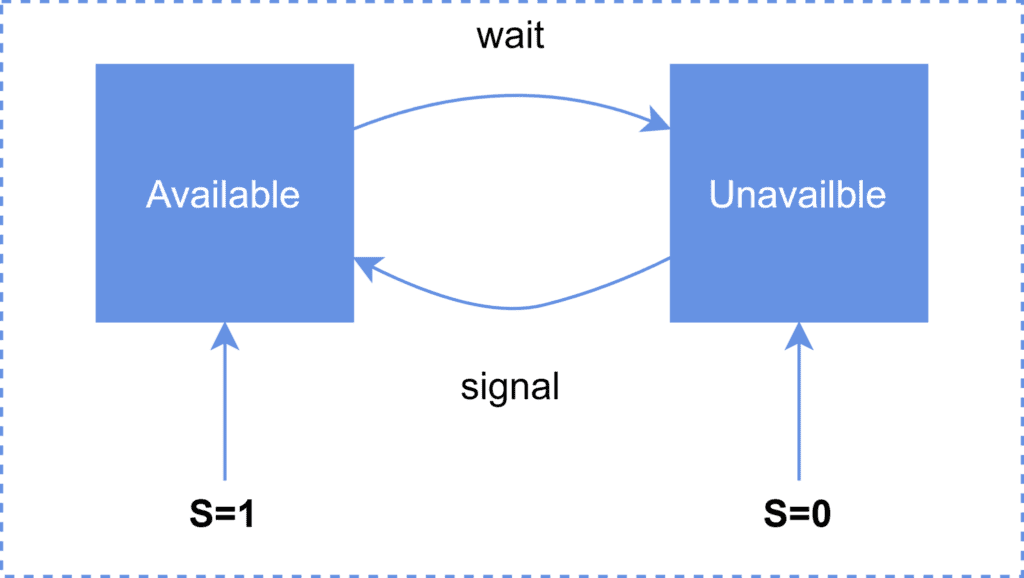

A binary semaphore has two possible values, 0 and 1. If the resource managed by the semaphore is available, then the semaphore value is 1. Otherwise, it is set to 0, indicating the resource is not available.

A binary semaphore has the same functionality as a mutex lock. Systems that do not support mutex locks can leverage binary semaphores to achieve the same functionality.

The following diagram illustrates the binary semaphore:

The following table summarizes the important characteristics of semaphore and mutex locks:

| Characteristics | Semaphore | Mutex |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Signaling mechanism | Locking mechanism |

| Data Type | An integer value | Is an object |

| Types | Semaphore is of two types – Counting and Binary | A mutex has no subtypes |

| Ownership | Value is changed by any process releasing or obtaining the resource | Object lock is released only by the process that obtained it |

| Operation | Value is modified using wait() and signal() operation | Object is locked or unlocked |

| Resource Management | Threads are not blocked unless the semaphore value reaches zero | Only one thread can use a mutex at any given point in time |

| Modification | Only the wait() and signal() operations can modify a semaphore value | It is modified by the process that is accessing the resource |

| Simultaneous Access | Multiple threads of a process can access a semaphore simultaneously | A mutex is not for simultaneous access |

In this article, we discussed various aspects of mutexes and semaphores.

First, we discussed the critical section and the need for a mutex or semaphore to control critical section execution. We then talked about mutex and semaphore.

Lastly, we provided a comparison of semaphore and mutex.