Learn through the super-clean Baeldung Pro experience:

>> Membership and Baeldung Pro.

No ads, dark-mode and 6 months free of IntelliJ Idea Ultimate to start with.

Last updated: May 19, 2025

Regular expressions (regexes) are powerful pattern-matching tools that can represent both simple and complex text patterns. We commonly use them for searching, validating, and parsing.

Among these patterns, (a+b)* and (a*b*)* may appear similar but behave differently, potentially confusing users. Understanding these differences is essential for adequately applying them in real-world scenarios.

In this tutorial, we’ll look at the differences between the expressions (a+b)* and (a*b*)*.

If we have an alphabet of only two symbols, a and b, which regular expression best represents all the strings we can make with these characters? We’ll consider two candidates: (a+b)* and (a*b*)*. At first glance, they appear to be similar because both involve a and b. However, their behavior differs depending on how we interpret the + operator.

Depending on the context, the + symbol can have two distinct meanings:

This difference in meaning produces confusion because it results in different answers to whether (a+b)* and (a*b*)* are the same.

In this section, the + operator denotes a union (logical “or”), following the common notation of the formal language theory. Therefore, a+b matches a or b.

The expressions (a+b)* and (a*b*)* can seem different at first glance, we’ll see they are equivalent in the formal language theory. They describe the strings we can form using the alphabet {a, b}, including the empty string ε.

The expression (a+b) specifies the union of sets {a} and {b}. It defines a language that solely uses the symbols a and b.

Applying the Kleene star * to (a+b) produces all possible sequences of these symbols, including the empty string ε. This means that (a+b)* includes strings such as a, b, ab, ba, aba, and so on, allowing for any sequence and number of repeats of valid patterns a+b.

The expression (a*b*) matches strings that start with zero or more a’s and end with zero or more b‘s. For example: aaa, bbb, aaabbb, and the empty string ε.

When we apply the Kleene star * to (a*b*), it allows for repetitive concatenation of such patterns. As a result, (a*b*)* accepts the strings such as aaa, bbb, aabbb, abab, and others.

3.3. Subset Relationship

To prove the equivalence of (a+b)* and (a*b*)*, we must show that the languages they describe are subsets of one another.

First, we can break any string described by (a+b)* into segments, with a‘s and b‘s grouped consecutively. Each segment fits the pattern (a*b*), demonstrating that every string in (a+b)* is also part of (a*b*)*.

Further, any string in (a*b*)* segment contains only a‘s and b‘s. Therefore, all the strings recognized by (a*b*)* are also the strings of the language of (a+b)*.

Therefore, (a+b)* and (a*b*)* are equivalent in the formal language theory.

In this section, we focus on the + operator as a quantifier for one or more pattern occurrences.

The regular expression (a+b)* looks for sequences with zero or more occurrences of the pattern a+b. In turn, that pattern denotes a string starting with one or more a‘s and ending with one b, including the empty strings:

import re

# Define the pattern

pattern = r"(a+b)*"

# Test some strings

test_strings = ["", "ab", "aab", "abab", "aabb", "b"]

for string in test_strings:

match = re.fullmatch(pattern, string)

print(f"String: '{string}' -> Match: {bool(match)}")

Let’s interpret the results:

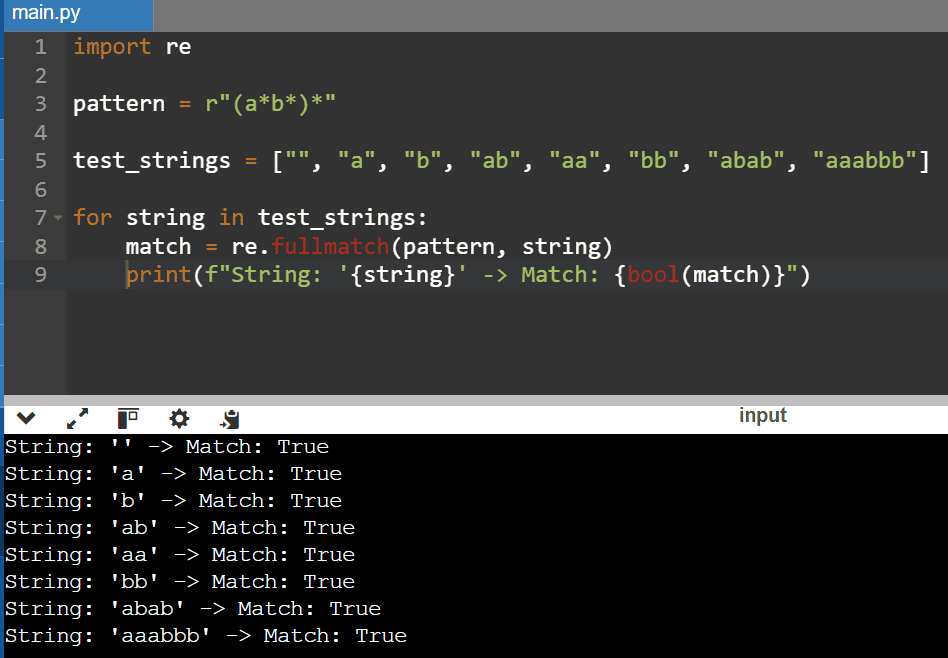

The structure of (a*b*)* is less rigid than (a+b)*. Each group (a*b*) can have zero or more a‘s and zero or more b‘s. The only rule is that a‘s must come before b‘s. The outer * quantifier permits the group to repeat an unlimited number of times, even zero. This means that the pattern can accommodate a wide range of sequences:

import re

# Define the pattern

pattern = r"(a*b*)*"

# Test some strings

test_strings = ["", "a", "b", "ab", "aa", "bb", "abab", "aaabbb"]

for string in test_strings:

match = re.fullmatch(pattern, string)

print(f"String: '{string}' -> Match: {bool(match)}")

From the formal-language point of view, (a+b)* and (a*b*)* are equal as both describe the language of strings containing a and b. However, other factors, such as readability, may influence the choice.

Furthermore, we must determine whether the empty string is considered part of the language. If we want to include the empty string, we keep the Kleene star (*). If not, we replace the outermost * with a postfix +, which represents “one or more.” To avoid confusion, we should use another symbol for the union (e.g., |) in this case. So, the expression will be (a|b)+.

In this article, we discussed the regular expressions (a+b)* and (a*b*)*.

They’re equivalent in the formal language theory if we interpret + as the union symbol. However, when + is used as a quantifier for “one or more,” these two expressions are different: (a+b)* matches the strings whose consecutive substrings contain at least one a and exactly one b in a strict pairing, whereas (a*b*)* allows for any number of a’s and b’s.