1. Introduction

In this tutorial, we’ll talk about error handling.

2. Errors

Let’s assume that we wrote a computer program that reads some values from an Excel file.

In the first step, the program will try to open the file. If the file exists at the specified path, the program will open it and read values. But, what happens if the file isn’t there? We encounter an error, or, in other words, an abnormal event our code should be able to handle without breaking.

3. Runtime Errors

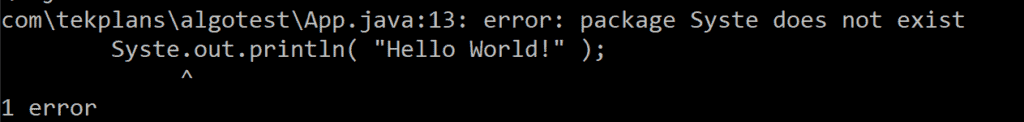

When we write a program, compile it, and run it, we may encounter errors. Some of them are detectable at the compile time. Examples of these errors are syntax errors that are mostly caused by typos. This category of errors is therefore called compile-time errors. For instance, we may type “Syste” instead of “System”, and get:

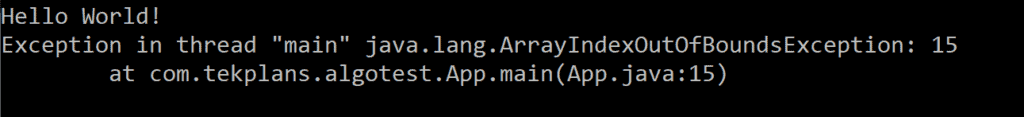

On the other hand, some errors can be detected only when the program is run. We call them runtime errors. For instance, we may try to access an element of an array at an index that doesn’t exist, such as element 15 in a 4-element array:

3.1. Some Cases of Runtime Errors

Runtime errors occur when a program is running and is therefore reading input data, doing computations, and writing output data.

Examples of read/write runtime errors are:

- Trying to access a missing file

- Waiting too long for a non-responsive network (timeout error)

- Accessing an array element beyond the array’s boundary

Examples of computation errors:

- Dividing a value by zero

- Producing a value outside the range of values for a certain type. This is called an overflow.

We cannot completely avoid such errors because they happen because of the runtime conditions, and we can’t control them. The best we can do is make our code resilient by specifying what it should to when it detects an error.

3.2. Detecting a Runtime Error

A computer system comprises both hardware and software. We may further divide the software components into operating system and applications. When a running program (application) needs to access computer hardware, it does so through the operating system. Or, more specifically, it calls a library function provided for the operating on which the application runs:

When an error occurs, one of the previously mentioned components may detect it:

- The hardware, e.g., the CPU, may detect a computation error, e.g., division by zero.

- The operating system’s library function may, for instance, detect a file access error.

- A function in an application may detect an input error, e.g., a user input a string instead of a number.

Of course, the detection may be done in various ways, depending on the design of the hardware/software. At the hardware level, digital circuits are responsible for the detection. The Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU) of a computer’s CPU may have logic circuits that detect some types of errors. For instance, in a division instruction, Motorola’s 68000 processor checks if the value of the divisor is zero. Some other processors may not perform this check. Consequently, software running on these processors will be responsible for detecting division by zero.

At the software level, we may detect errors by testing the value of some expression. So, a function performing division will have to test the value of the divisor to check if it is zero.

The component detecting an error should announce its occurrence. By doing so, it notifies other components, which may then take some action.

3.3. Announcing a Runtime Error

If a CPU detects an error, it announces it by setting the corresponding register bit or generating an interrupt. For instance, the Intel x86 processors have a register called EFLAGS. One of the bits of this register is set to 1 if an arithmetic operation causes an overflow.

At the software level, when a function detects an error, there are two options to announce it:

- Return a value that indicates the occurrence of the error.

- Raise (throw) an exception.

As an example of the first option, a function may return a value of -1 when it detects an error. Of course this implies that the function would never return the value -1 in normal conditions.

The second option is throwing an exception. Programming languages that support exceptions, provide mechanisms for:

- Raising or throwing an exception, thereby announcing the detection of an error.

- Finding out if any exceptions were raised.

- Performing some action, if a raised exception is found.

The last step above is called handling the raised exception.

3.4. Handling an Exception

Let’s consider a function that performs some operation while also checking for possible errors. What does it have to do?

- First, check if the error occurred by testing the value of some expression.

- If the error occurred, the function should should announce the error by throwing an exception.

- The caller should check if an exception was actually thrown.

- Then, it should handle it by executing the exception handler, which is the code snippet specifying what should be done when that exception is thrown.

We call steps 3 and 4 catching an exception. This is the flow of throwing and catching exceptions:

4. Hierarchy of Exceptions

Exceptions are either built-in or user-defined.

The runtime system of some languages, like Java, defines several classes of exceptions. We can use them without worrying about their inner-workings. However, we can also define our own exceptions by sub-classing any of the pre-defined ones. So, there is usually a hierarchy of exceptions.

4.1. Matching the Exception

We can use the exception’s type to choose the right handler. Let’s assume that we have multiple throw statements, where the exceptions are of different types. If we need to handle each exception differently, we’ll have multiple handlers in multiple catch blocks. The previous figure illustrates this, where the type of exceptions may be one of n types.

The match between an exception and a handler is then done using types. An exception of type T will be handled by the catch block whose formal parameter is of type T, or any parent (ancestor) of T in the hierarchy of exception classes.

5. Exceptions in Nested Function Calls

A function might have a throw statement without a matching exception handler. In this case, it can’t handle a thrown exception. The exception will therefore escape the function, which will terminate. This is illustrated at the bottom of the previous figure. The runtime system will then need to free the stack frame assigned to this function. The exception itself may however propagate to other functions in search for a handler.

5.1. Example

Let’s assume we have a function F that calls function G which, in turn, calls function H, and so on till we end up some function K. Now, let’s suppose the last function in this sequence, i.e., function K, throws an exception. This exception may not be handled in K for one of two reasons:

- K contains only a throw statement without an exception handler.

- There are multiple exception handlers in K but none of them matches the type of this specific exception.

In this case, function K terminates, and the runtime system propagates the exception up the calling sequence in search for a handler:

In each function in the sequence, the runtime system tries to match the exception with a handler. If one is found, it will be executed. If not, the exception escapes this function. The runtime system will terminate the function and free its tack frame. The exception will then be propagated further up the calling sequence. If no function can handle the exception, the whole program will terminate.

6. Conclusion

In this article, we talked about error handling using exceptions. We have seen how exceptions are raised, detected, and handled. They should allow our code to be able to recover from various runtime errors, not just detect them.