Yes, we're now running our Black Friday Sale. All Access and Pro are 33% off until 2nd December, 2025:

Explaining the Context Design Pattern

Last updated: March 18, 2024

1. Overview

In this tutorial, we’ll discuss the patterns utilizing the idea of context. These patterns have several interpretations as it isn’t part of the GoF classic pattern.

2. Encapsulate Context

This version of the context-related patterns addresses two main problems: the number of parameters and uniform interfaces.

2.1. Reducing the Number of Parameters

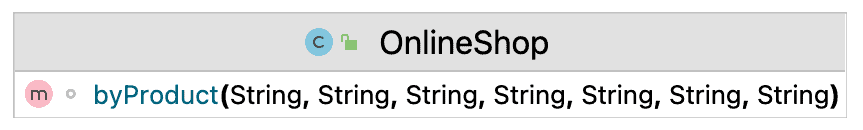

One use case for this version is to reduce the number of parameters passed to a method. Let’s say we want to buy a product, but we need to provide information about the customer, delivery, payment method, and so on:

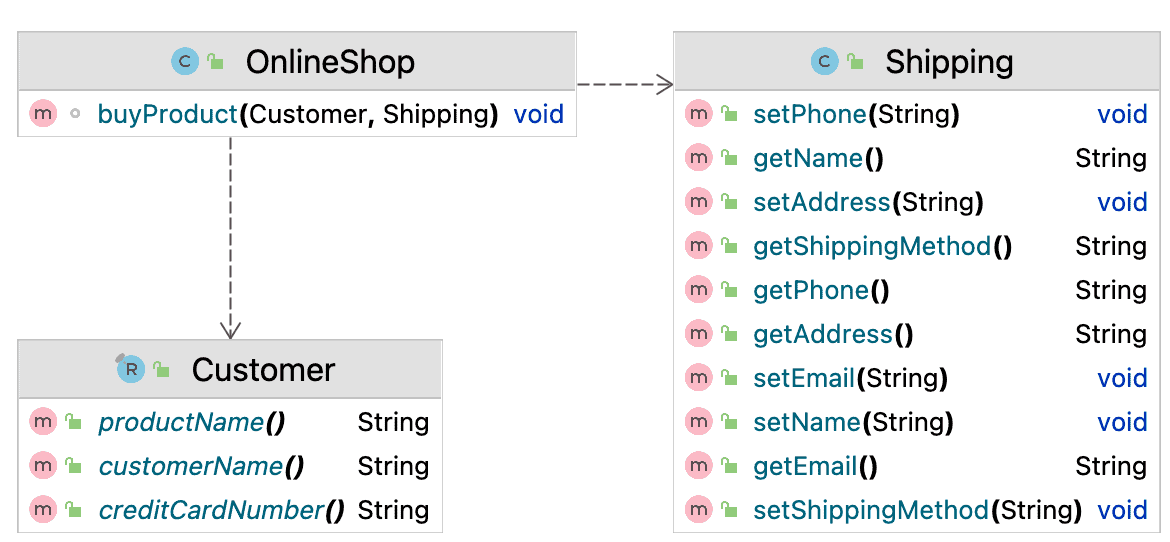

The Encapsulate Context is unsuitable for this case. We should use the Parameter Object or the Introduce Parameter Object, which has the same idea of organizing parameters inside a container. The elements grouped using these patterns are usually closely related to each other:

Note that the Introduce Parameter Object is a refactoring pattern used as a step rather than the end goal.

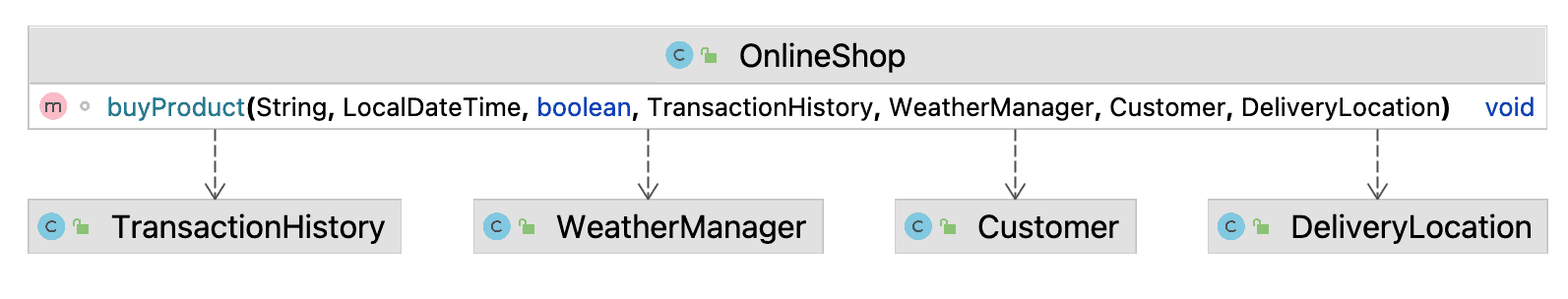

Encapsulate Context can be used to resolve the issue when parameters are unrelated:

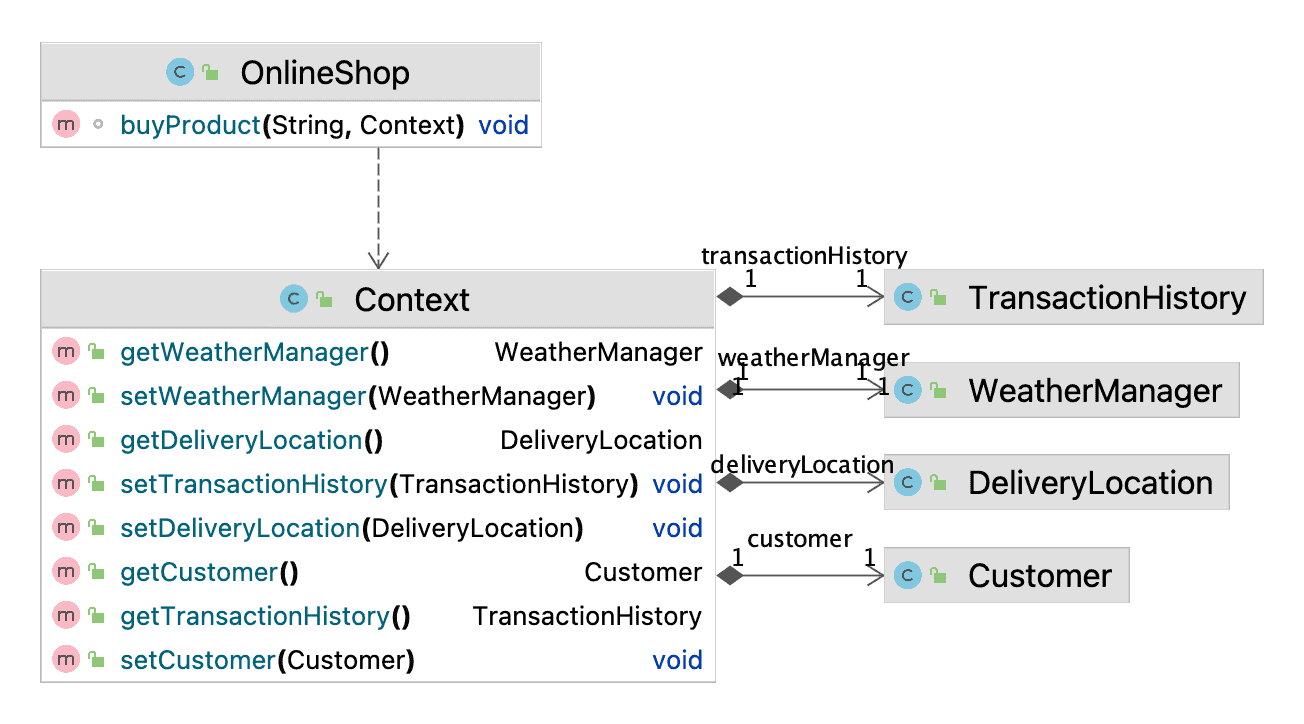

There’s no appropriate object in the application domain to group these parameters. That’s why some abstract container is appealing in this case:

We can identify this approach because the context components have little to do with each other. This solution may provide beneficial results, but certain aspects of this pattern make it fragile and could turn the Context into the Blob.

2.2. Uniform Interface

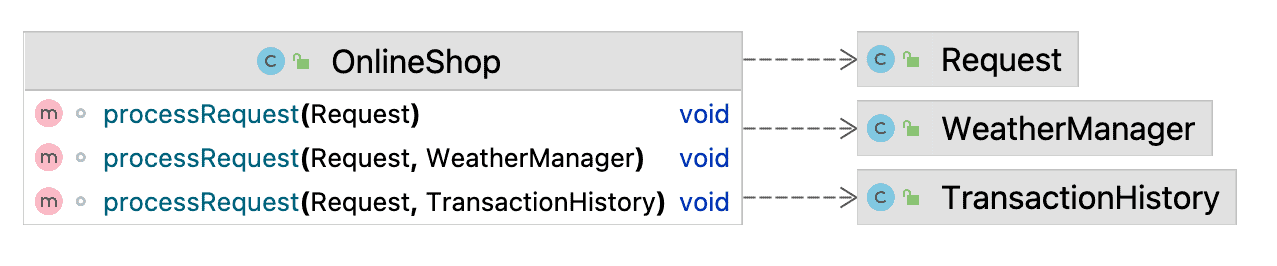

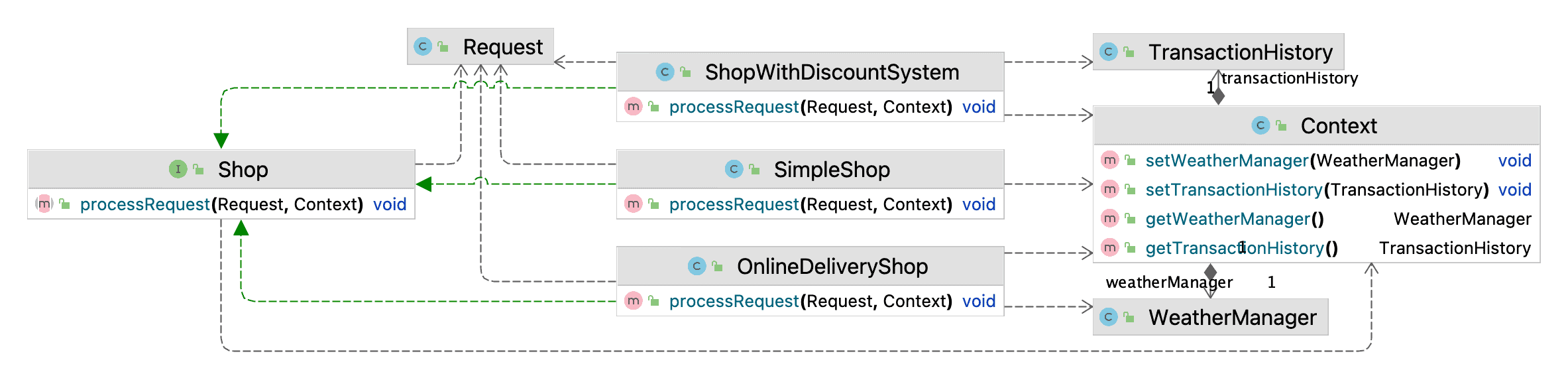

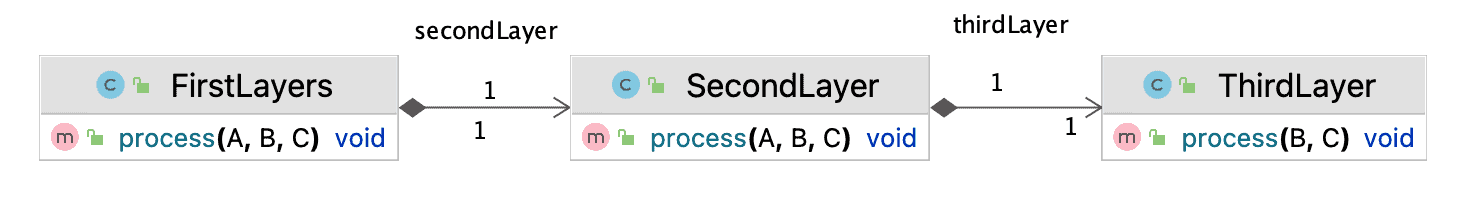

Another described use case tries to achieve a uniform interface between methods. Let’s assume we’d like to split our OnlineShop class into three subclasses under one interface. Also, we’d like to distribute the methods in separate implementations:

Achieving this is much easier when all the components are hidden in the Context. All we need to do is provide the interface to pass the context:

Using the Encapsulate Context this way inherits all the problems with the Service Locator. At the same time, this issue shouldn’t be resolved by the Parameter Object as in the previous case. We should rethink our design and question the idea of adhering to different methods for the same interface.

2.3. Use Cases

While this pattern is useful in certain situations and may help to understand the code easier, Encapsulate Context is fragile and requires a thoughtful approach. It may provide a good separation between the data needed by an object and the data shared by the entire application. However, it’s easy to breach this line and implement the Blob.

Also, hiding the data inside a container makes the code less readable and harder to follow. Seemingly unrelated changes in one part of the application may cause problems in the other.

Testing is possible, but often it would require checking the source code. With this pattern, the interfaces don’t provide enough information about which components are used in tested objects. At the same time, tests share the previous problem: changes in one part of the application may break tests for another.

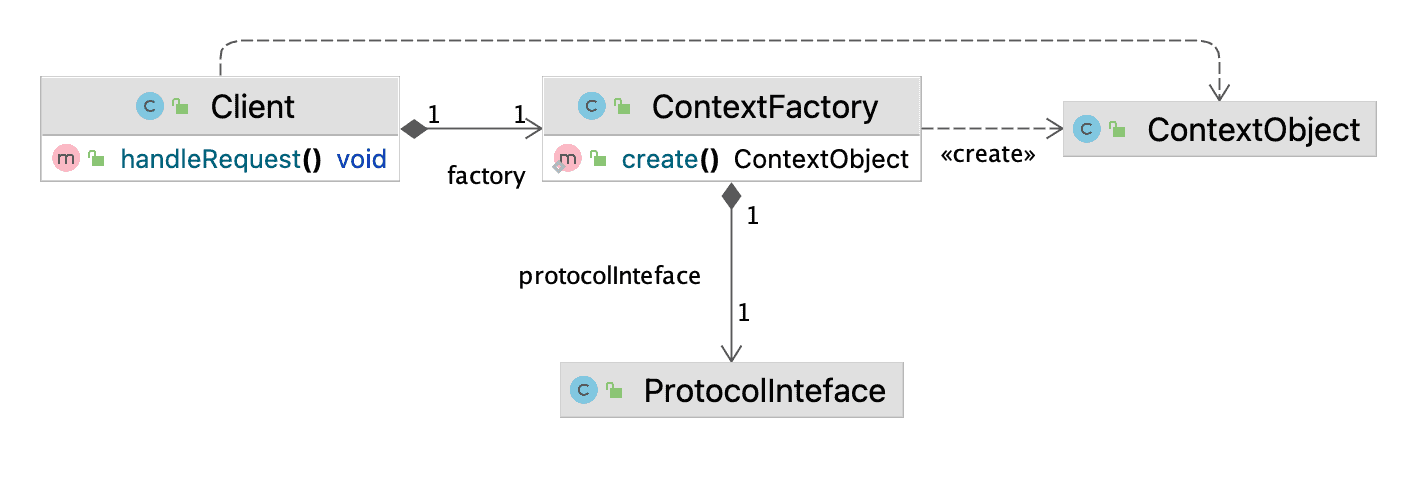

3. Context Object

Context Object aimed to provide a protocol-agnostic way to interact with global or contextual data. It’s a reasonable way to protect the application from relying on implementation details and make it more flexible:

This implementation uses a single part of the application as the source of the ContextObject and is very close to the Adapter Pattern or the Facade Pattern. It’s an excellent way to make the application more flexible and protect it from any changes in the protocol itself.

4. Context Pattern

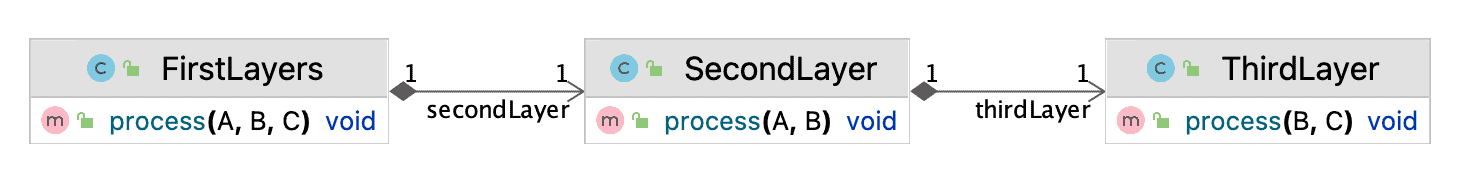

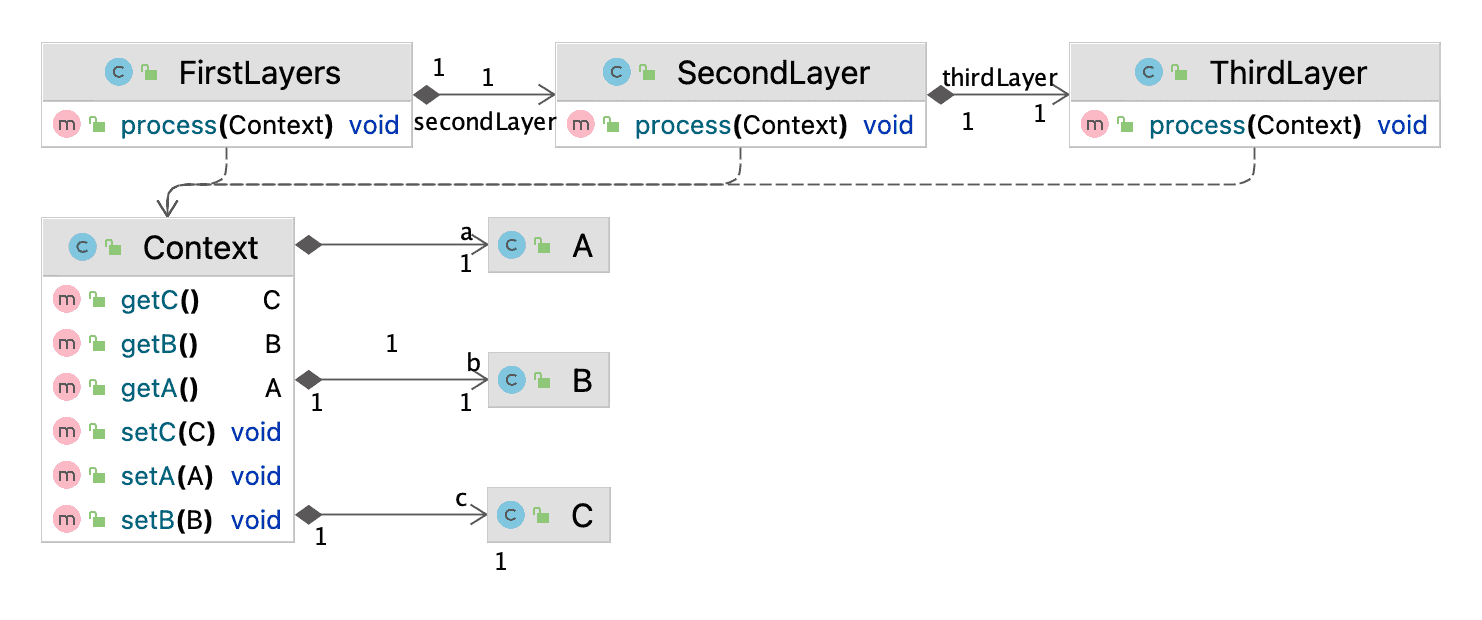

This approach was proposed by Douglas C. Schmidt. Let’s take an application with three layers as an example:

4.1. Passing Information Through Layers

The main problem with these layers is that the third layer depends on object C used in the first layer. At the same time, the second layer doesn’t need it. Let’s resolve this problem by simply passing C through the second layer:

The last layer needs the information received by the first, which highlights the problem with the transitive dependencies between layers.

Note that the original pattern aimed not to eliminate or make the dependencies less transparent. The problems it addresses are more complex: performance improvement, simplifying the application’s data management, and allowing greater flexibility in a middleware application. Thus, it’s used in a particular environment. Here we’ll discuss the problems with this approach in more typical applications.

4.2. Context

The central premise for the Context Pattern is that each application layer relies not only on immediate neighbors. The idea is to create a Context and allow each layer to access and alter it. We can pass the Context through the layers or make it global:

This approach removes compile-time dependencies between layers, making changes and refactoring easier. However, hiding the information in the Context doesn’t resolve the transitive dependencies and makes them invisible. At the same time, it might improve the application’s performance as fewer parameters are passed around and also allows for easier caching.

4.3. Stamp Coupling

On the negative side, the Context binds unrelated objects because they depend on it. This is known as Stamp Coupling. In this case, it has a bit of abstraction over it. In Layman’s terms, Stamp Coupling is the assumption that all classes that use Context are related, which might be true for some and false for others. This way, the Context is similar to the Service Locator and has similar adverse effects.

Using the Context for performance improvements or specific requirements might be a reasonable and quick solution. It might help when the lowest layer depends on the information created beyond the immediate neighbors. However, in the long run, it might have a very detrimental effect on the codebase. Also, this might indicate the layers’ design needs to be improved.

This approach risks making the relationships between classes and layers too opaque and fragile. Seemingly unrelated changes in the context elements may cause issues in different layers where these values were used. Often these problems reveal themselves only at run-time. Thus, we should be careful about the design of the Context and treat it with caution, as it might affect all the layers of the application.

4.4. Taking Additional Responsibilities

In addition to the previously described problems, the Context can bloat as it’s a perfect place to add dependencies. It’s easy not to think about architecture or design when everything is magically available from the Context.

Another thing is that the Context can start to play the Observer role and take communication responsibility, which isn’t its initial purpose. However, as the Context has access to all the layers and components, it can be used this way.

All the problems with this pattern come from the fact that it doesn’t have clear boundaries, and developers can abuse it. Overall, it makes sense only as a quick fix to an urgent problem, as a step in refactoring, or in some specific cases with well-defined responsibilities of the Context.

5. Conclusion

In this article, we discussed several patterns that utilize the idea of context. Several use cases for these patterns should be used cautiously. Often, these patterns are applied to applications with very specific requirements. However, this fact doesn’t cancel their drawbacks. In most cases, they should be avoided entirely as they might make the codebase fragile and the code harder to follow.